Those watching the ongoing Euro-mess might be surprised at a policy recommendation that the Fed should behave more like the ECB. That’s what Republican Senator Bob Corker does in today’s FT. My comments here.

Monthly Archives: August 2012

Note to Republicans: The US Can’t Do a Gold Standard On Its Own

Outside my usual set of topics but apart from enthusiastic goldbug types, I hadn’t seen anyone else discuss the Republican proposal to link the dollar to the value of gold. Comments here.

ECB Secret Letter to Ireland To Be Released?

Proof perhaps that sometimes even a humble blog post can have some impact, it appears that we have had some movement on the question of the ECB’s secret letter to Ireland. Some further comments here.

Greece: We Need to Stop Confusing Default with Exit

The debate about “Grexit” continues to confuse the question of the sustainability of Greece’s debts with the question of whether Greece should stay in the euro. Some comments here.

The ECB’s Secret Letter to Ireland: Some Questions

By announcing it is only willing to purchase Spanish and Italian government bonds if these governments apply for funding from the EFSF bailout fund, the ECB is now exerting pressure on these countries to sign full bailout agreements. Officially,Mario Dragih’s position on how the ECB engages with governments (as explained at his June press conference) is

I do not view it as the ECB’s task to push governments into doing something. It is really their own decision as to whether they want to access the EFSF or not.

In reality, the record of the ECB’s role in Ireland’s bailout application (admittedly at the time under the leadership of Draghi’s predecessor) suggests it is an organization that is not at all averse to pushing governments into bailout funds. As the facts below illustrate, this record also doesn’t provide encouragement that the ECB will act in an open and transparent manner when doing so.

In the months leading up to Ireland’s bailout agreement, the ECB had become increasingly concerned about the amount of money it was loaning to Irish banks. In early November, it appears the ECB decided it needed to intervene.

On Friday November 12, 2010, Reuters reported that Ireland was in talks with the EU to receive emergency funding. The Irish government denied that any official talks were taking place. However, Brian Lenihan, Ireland’s Minister for Finance at the time, subsequently told a BBC documentary that, on this same day he received a letter from Jean-Claude Trichet advising him that Ireland should enter an EU-IMF program. Lenihan was adamant that “the major force of pressure for a bailout came from the ECB”.

The Irish Times has reported that

Dublin officials believed the letter to be forthright, with an implicit threat that support for Ireland’s banks was at risk.

Alan Ahearne, Lenihan’s economic adviser at the time, confirmed these reports to the Irish Independent:

“Yeah, the letter came in on the Friday from Trichet. The ECB were getting very hostile about the amount of money that it was having to lend to Ireland’s banks. The ECB demanded something be done about it and it mentioned Ireland going into the bailout. They were keen to get Ireland into the programme.”

He added: “Lenihan rang Trichet that day, and they agreed officials would meet the following day in Brussels. When they met, the ECB put huge pressure on Ireland to go into the programme.”

Ahearne said Lenihan was now at the centre of international chaos and Ireland’s future hung in the balance.

“The following Tuesday, Lenihan went to the eurozone meeting …”

The Independent story does not state the date of arrival of Trichet’s letter but the reference to a Eurozone meeting on the following Tuesday confirms November 12 as the date.

Within weeks of the receipt of this letter, Ireland had entered an EU-IMF financial assistance programme. Given the key role the ECB letter of November 12 appears to have played in such an important event in Europe’s economic history, one might hope that this letter would now be in the public domain. However, the letter has not been released.

Last December, an Irish journalist, Gavin Sheridan requested that the ECB provide him with “any and all communications from the ECB addressed to the Irish finance minister (or his direct office) in the month of November 2010”.

The ECB responded by supplying one letter dated November 18 (a technical communication relating to payments systems) but refused to supply another letter that dated November 19 (one week after the Reuters story and one day after Central Bank of Ireland Governor Patrick Honohan conceded that a bailout deal was likely).

The ECB’s justifications for not releasing the letter included the following paragraph:

The second letter, dated 19 November 2010, is a strictly confidential communication between the ECB President and the Irish Minister of Finance and concerns measures addressing the extraordinarily severe and difficult situation of the Irish financial sector and their repercussions on the integrity of the euro area monetary policy and the stability of the Irish financial sector.

The content of the letter was alluded to as follows:

The ECB must be in a position to convey pertinent and candid messages to European and national authorities in the manner judged to be the most effective to serve the public interest as regards the fulfilment of its mandate. If required and in the best interest of the public also effective informal and confidential communication must be possible and should not be undermined by the prospect of publicity. In this case, the confidential communication was aimed at discussing measures conducive to protecting the effectiveness and integrity of the ECB’s monetary policy and fostering an environment that ultimately contribute to restoring confidence among investors in the overall solvency and sustainability of the Irish financial sector and markets, which, in turn, is of overriding importance for the smooth conduct of monetary policy.

These communications raise a number of questions:

- Did the ECB communicate with Brian Lenihan on November 12, 2010? If so, why was this letter not referred to in response to Mr. Sheridan’s request?

- Did the ECB threaten to withdraw funding from Irish banks unless Ireland entered an EU-IMF program, either in a letter dated November 12 or in meetings the following weekend?

- What are the contents of the November 19 letter and why is this letter considered so sensitive given that it was clear to all after Governor Honohan’s remarks on November 18 that a bailout deal was being concluded?

I believe the Irish and wider European public deserve a better explanation of the events of November 2010 from the ECB. The public release of all communications from Mr. Trichet to Minister Lenihan should be part of this explanation.

Europe Needs to Change Its Disastrous Policy on Greece: Here’s Why and How

There has been a marked increase in the number of European politicians talking about a Greek exit from the euro. I think much of this commentary is based on resentment and a mis-understanding of the facts. Thoughts here.

Would A Greek Exit Really Be Manageable?

Jean-Claude Juncker, Luxembourg prime minster and head of the Eurogroup of finance ministers has said that he believes that a Greek exit from the euro would be “manageable” Partially based on my recent experience of Ireland’s banking crisis, which was “manageable” until suddenly it wasn’t, I don’t take much reassurance from politicians using this phrase.

In many ways, this was a fairly typical intervention from Juncker, who has a touch of foot-in-mouth disease. His comments appear to have begun as a dismissal of German politicians saying they are not worried about Greek exit with Juncker pointing out “it would be better if more people in Europe kept their mouth closed more often”. Indeed. But then this particular piece of reassurance comes from the man who, when caught lying last year about an emergency finance ministers meeting on Greece, responded “When it becomes serious, you have to lie.”

So what’s the case for a Greek exit being manageable? One could argue that the euro existed for a time without Greece and functioned fine, that allowing Greece to join was a mistake, and thus that a euro without Greece would be more stable. While some of the countries that would remain in the euro also have severe debt problems, you could argue that they were not as intractable as Greece’s.

Finally, you could argue that the Eurosystem would provide full support to the governments and banks in the remaining countries provided, of course, that they don’t go the Greek route and fail to control their debt problems. In other words, some believe a Greek exit could reinforce the rules required to maintain the stability of the euro by showing that the core countries are serious about their enforcement.

I think these arguments under-estimate the seismic impact a Greek exit would have and I have severe doubts as to whether these impacts could be managed in a way that saves the euro.

A Greek exit would forever shatter the illusion that the euro is a fixed and irrevocable union. European politicians will claim that Greece is a unique case but they have made far too many false claims in the past to be considered credible.

A Greek exit would likely trigger a massive flight of bank deposits from the periphery as the current “bank jog”—largely driven by large corporate accounts and non-residents—turns into a full retail bank run. If default on deposits is to be avoided, this would require a massive injection of central bank funding by the Eurosystem into these countries. This would raise severe tensions: Will Germans be willing to allow the Banca d’Italia to print enormous amounts of euros to facilitate Italians to move their money to Germany and have their deposits stand on an equal footing with German resident deposits after a euro break-up?

Another possible response to a bank run would be the introduction of euro-wide deposit insurance. However, this plan would only work provided it guaranteed that people retained the original value of their euro deposits even after they had been re-donominated into pesetas or lira. Otherwise, people will still have an incentive to move their money. But re-denomination insurance provides a huge incentive for countries to leave. People can have their debts re-denominated into a weaker currency and the EU will kindly pick up the tab in relation to the money people lose on their deposits. This proposal would not be acceptable to the core Eurozone countries.

A Greek exit would trigger a broad range of different legal problems as various parties sue each other to claim they are owed euros, not drachmas. The resolution of these problems would illustrate which kinds of parties are at risk when a country exits the euro and their Spanish and Italian counterparts would come under severe pressure.

A Greek exit would place pressure under peripheral Eurozone economies no matter what the outcome is. A disastrous post-euro outcome in Greece will convince many investors that any economy in the euro area at risk of leaving should be avoided. Alternatively, a healthy Greek rebound after the initial chaos would place pressure on governments in countries suffering inside the Eurozone that Greece is an example to be followed.

The European authorities may have some secret plan for holding the euro together after a Greek exit but, frankly, I have my doubts.

Is the ECB Risking Insolvency? Does it Matter?

After Mario Draghi’s hints that the ECB is getting ready to purchase large quantities of Spanish and Italian bonds, expect to read lots of commentary claiming “the ECB is taking huge risks with its balance sheet”, that “the ECB risks becoming insolvent, endangering the future of the euro” or that “Eurozone states may have to recapitalize the ECB at huge cost to taxpayers”.

Much of this commentary is based on misunderstanding the facts about the Eurosystem’s balance sheet and the meaning of central bank balance sheets. In this post, I want to briefly explain what a central bank balance sheet is, then go through the basic facts about the capital position of the Eurosystem of central banks and then argue that the common focus on central bank solvency is misplaced.

Central Bank Balance Sheets

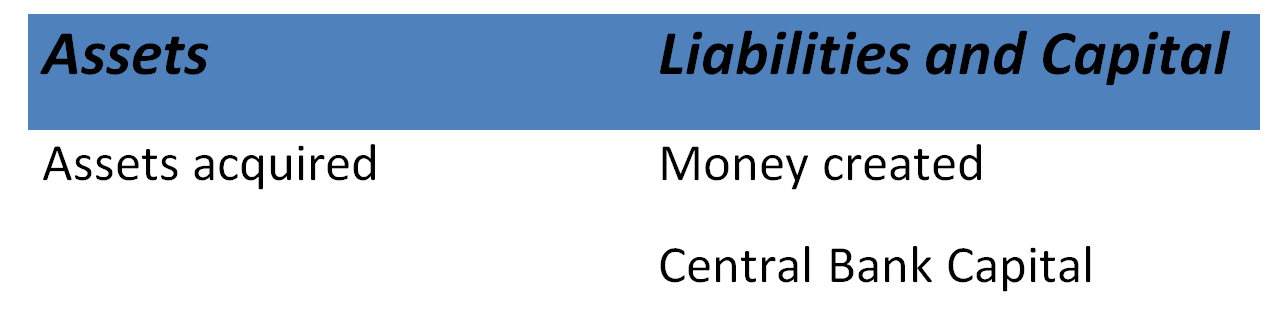

Like all businesses, central banks publish balance sheets that show their assets and liabilities. However, central banks are not just any business. They have the power to print money that is accepted as legal tender. So their assets have been acquired via printing of money. Central banks list the money they have created as liabilities and the gap between the current value of their assets and liabilities is labelled “capital”.

So a stylized central bank balance sheet looks as follows.

If a central bank purchases assets that then decline in value, it could end up having negative capital. When a commercial bank has negative capital, it is termed insolvent and either re-capitalised or shut down. The “insolvent” terminology is sometimes applied to a central bank in this situation but, as I discuss below, central banks are unique organizations and this phrase isn’t particularly appropriate.

Bond-Buying Risk: Eurosystem not ECB

A common confusion that arises when people discuss potential losses stemming from sovereign bond purchases or loans to banks comes from the assumption that the risk of these operations lies with the European Central Bank. For example, it is common to see commentary that examines the ECB’s balance sheet and concludes that the ECB faces a significant risk of becoming insolvent. This is because the ECB lists “Capital and Reserves” of only €6.5 billion, a tiny amount relative to the likely scale of bond purchases likely to be executed under the Securities Market Programme (SMP).

In fact, the ECB also has revaluation accounts and provisions, both of which can cover losses, worth €30 billion. More importantly, the risks associated with the bond-buying program are in fact shared across the ECB and all of the national central banks in the Eurosystem. So what matters when thinking about the threat to solvency of the SMP is the size of the Eurosystem’s capital resources.

The ECB releases a Eurosystem financial statement every week. Currently, it shows capital and reserves of €86 billion and revaluation reserves of €409 billion. These figures show the Eurosystem would have to incur much larger losses on its bond purchases than is often believed before the question of insolvency would become an issue.

Would Eurosystem Insolvency Matter?

This still raises an interesting question. What would happen if the ECB published its weekly balance sheet one day and it showed negative capital? For many commentators, the answer is apocalyptic. The euro will have lost all credibility as currency, hyper-inflation will ensue, that kind of thing.

In truth, the answer is that not much at all would happen. The euro is a fiat currency. In other words, unlike the days of the gold standard, the Eurosystem does not promise to swap the euro at some specified rate for another asset such as gold. The currency is not “backed” by the central bank’s assets.

Since central bank money costs next to nothing to create, the “Liabilities” on its balance sheet are essentially notional. Indeed, a central bank’s asset holdings could fall below the value of the money it has issued – the balance sheet could show it to be “insolvent” – without impacting on the value of the currency in circulation. A fiat currency’s value, its real purchasing power, is determined by how much money has been supplied and the various factors influencing money demand, not by the stock of central bank assets.

Taken to an extreme, one could argue that a central bank with sufficiently negative capital could face problems implementing monetary policy because its stock of assets may be so low as to limit its ability to sell assets to reduce the supply of privately circulating money. However, detailed analytical research by ECB economists Ulrich Bindseil, Andres Manzanares and Benedict Weller concludes that

central bank capital still does not seem to matter for monetary policy implementation, in essence because negative levels of capital do not represent any threat to the central bank being able to pay for whatever costs it has. Although losses may easily accumulate over a long period of time and lead to a huge negative capital, no reason emerges why this could affect the central bank’s ability to control interest rates.

Despite the absence of reasons to be concerned about negative central bank capital, it is still unlikely that such an outcome would be allowed to continue in the Eurozone. The actual rules relating to central bank solvency seem a bit murky but it is generally understood that any element of the Eurosystem that had negative capital would need to be recapitalized by governments providing them with assets.

Even then, these “recapitalizing” transactions wouldn’t actually have any effect on the net asset position of Eurozone governments because central banks hand over their profits to the government. For example, suppose a government hands its central bank a bond that pays €500 million in interest each year. That raises the net income of the central bank by €500 million and thus raises the amount that is handed back to the government by €500 million. The bond has no net cost to the government.

By these comments, I’m not suggesting that bond purchase programs have no cost. To the extent that they involve increasing the money supply, they can contribute to inflation so there is an implicit cost for all citizens. But this is the reason central banks need to be careful with their purchases; concerns about central bank solvency are beside the point.

Unfortunately, despite its lack of substantive importance, the idea that the Eurosystem needs to be protected from balance sheet insolvency has featured heavily in discussions of policy options. Indeed, it is well known that senior ECB officials are extremely concerned with protecting their balance sheet and have employed their “risk control framework” to protect themselves from losses at many of the key moments in the euro crisis.

One can only hope that the policy debate about the upcoming bond purchases focuses on things that matter, like the future of the euro, and not on things that don’t, like the ECB’s capital levels.

Some Saturday Euro Crisis Readings

Some useful links and readings from this week.

ECB : We’ll Do What It Takes. Kinda. Sorta. Later.

My thoughts on today’s ECB Governing Council announcements are here.