In the past week, I’ve come across two different pieces (one by the BIS and one by the UK’s Office for Budget Responsibility) warning that the maturity of public debt in advanced economies has been shortening and this could have fiscal implications during a recovery.

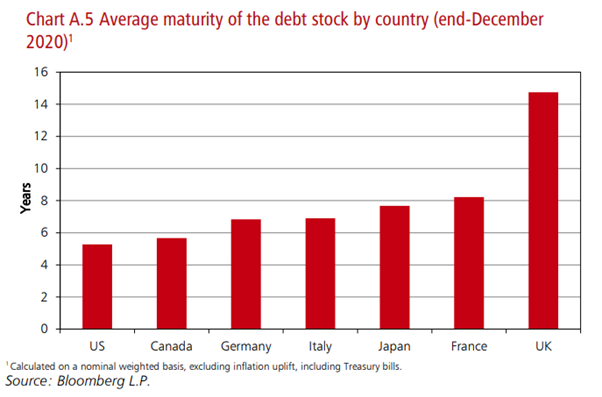

This warning might seem surprising since the Covid crisis and the low long-term interest rates of recent years have seen governments issue lots of long-term debt. Indeed, conventional measures of average public debt maturity are increasing. In the euro area, the average maturity of public debt has increased from about six years a decade ago to about 8 years now. In the UK, the average debt maturity is a whopping 15 years.

So what are the BIS and OBR talking about? They come up with different numbers by calculating an average maturity that includes reserve balances held by commercial banks at central banks. These reserve balances are generally compensated by central banks using their short-term policy rate and BIS and OBR are treating them as overnight debt when doing their average maturity calculations.

The BIS say about central bank asset purchases

Considering the consolidated public sector balance sheet, these operations retire long-term government debt from the market and replace it with overnight debt – interest bearing central bank reserves. Indeed, despite the general tendency for governments to issue at longer maturities, central bank purchases have shortened the effective maturity of public debt. Where central banks have used such purchases more extensively, some 15–45% of public debt in the large AE jurisdictions is in effect overnight.

Similarly, the OBR’s calculations show the median maturity of UK debt falls from 11 years to 4 years if you include reserve balances as an overnight liability. As an aside, I’m not sure median maturity is particularly interesting. If half my debt is due in 2 years, then that’s the median maturity. But it does matter whether the other half is due in 3 years or 100 years. I suspect median maturity has been chosen here for dramatic effect.

There are two reasons to worry about a shortening maturity for government debt. First, short maturities raise the probability of some kind of funding crisis. If the debt is all due relatively soon and investors decide not to roll over their funding, then there could be a debt crisis requiring a sovereign default and\or a large fiscal adjustment.

Second, and less dramatically, if the economy recovers and central banks raise interest rates, then the short-term debt will re-price at these higher interest rates and raise interest costs for the government.

Should we be worried? I don’t think so.

Rollover Concerns

I’ve always been uncomfortable with the labelling of central bank reserves as liabilities. Yes, in recent years, central banks have chosen to pay interest on them but they get to choose that interest rate and it can be zero if they want it to be. These are not debts that look like a normal person’s debts. But whatever about the labelling, I don’t think you can legitimately include central bank reserves in an average maturity calculation designed to measure potential debt rollover pressures.

These reserves are created by central banks to pay for asset purchases and there is nothing the banking system can do to get rid of them. An individual bank might be unhappy with having so much on reserve with the central bank but if they try to get rid of them by buying a security or extending a loan, their reserves just end up with another bank. As Ben Bernanke said, they’re like a hot potato.

Given this, there is no direct comparison between a sovereign bond maturing and an overnight reserve balance “maturing”. The owner of the maturing sovereign bond has to be paid and the money must be found from somewhere to pay it off – either the government’s existing cash balances or via new borrowing. In contrast, the banking system cannot demand that its reserves be “paid up.” In any case, the reserves already essentially are money and they can be turned into cash on demand.

So the risk of funding crises for most advanced economies is minimal and the real story of recent years is that governments around the world, but particularly in the UK, have locked in lots of very long-term low-interest debt.

Rising Interest Costs

This is, on the face of it, a more legitimate concern. Central banks used to raise interest rates by generating an artificial shortage of reserve balances, thus increasing the market interest rate paid to borrow these balances. In an age where reserves are in huge excess supply, this method doesn’t work anymore. Instead, central banks raise market interest rates by increasing the interest rate they pay on reserve balances to commercial banks and this rate then acts as a floor on market rates.

If central banks end up paying high interest rates on their reserve balances while holding a portfolio of long-term fixed rate bonds, then in theory, the central bank could start to make losses as interest paid exceeds interest earned. This could reduce their remittances back to central government and thus have fiscal effects. Taken to an extreme, there could be a scenario where there needs to be payments in the other direction because the central bank has so little money left it can’t fulfil its interest on reserves policy.

Thankfully, there is no need to worry about this stuff. Crucially, we know now that central banks can affect market interest rates without compensating all reserve balances. The Bank of Japan and the ECB operate a tiering system in which the interest rate on reserve balances is zero up until a bank’s reserves reach a certain level and then an interest rate is applied on those remaining balances. This keeps the marginal cost of funds in the economy at the policy rate while detaching the policy rate from the average cost of remunerating reserves. Currently, these central banks have a negative policy rate but tiering could be operated in future to raise interest rates without having much impact on the central bank’s profits.

Even if central banks decided to continue paying the policy rate on all reserve balances, there are reasons not to be too concerned. While reduced central bank profits during a monetary tightening are possible, outright losses are less likely. A 2015 Federal Reserve study simulated a sharp monetary tightening and concluded there may need to be a few years when the Fed reduced remittances to the Treasury to zero but the overall impact was relatively small. There are also other assets held by central banks that will provide an increased return as interest rates rise. For example, the interest payments on reserves created by the Eurosystem to make loans to banks are always more than offset by the higher interest payments charged on these loans.

So you could argue that technically neither the BIS or OBR are outright wrong about the maturity of “consolidated public liabilities” but there are good reasons to not be concerned about the points they raise. And claims about “ticking debt bombs” from the usual austerity cheerleaders should be taken with a massive dollop of salt.