This Thursday, the UK government will introduce a budget with significant tax increases and spending cuts. The UK press are largely reporting this as necessary to close a “black hole” in the UK’s public finances. It is frequently suggested that much of this black hole is a direct result of the fiscal profligacy proposed by the short-lived Truss government. The reporting generally suggests that a contractionary budget is a matter of common sense—books need to be balanced and after September’s chaotic events, the new government needs to demonstrate to financial markets that it is serious about fiscal discipline.

I disagree with this assessment. In fact, with the UK economy clearly tipping into recession, a large fiscal contraction is not common sense. It is certainly not what textbook macroeconomics would call for. Here, I discuss a few different aspects of the UK’s fiscal black hole, question whether austerity is necessary and point to one concrete alternative to spending cuts and tax increases as a way to reduce much of the projected budget deficit over the next few years.

It’s a long post so let me tell you how it is structured.

First, I describe what the UK’s fiscal “black hole” actually is and how it results from a series of essentially arbitrary fiscal targets rather than from a genuine crisis that must be urgently addressed.

Second, I argue against the widely promoted idea that the Truss-Kwarteng interlude showed that financial markets need to see a big fiscal adjustment now and that there would be further disruptions if we don’t see a harsh austerity programme on Thursday.

Third, I discuss two technical issues relating to the Bank of England which have had a significant influence on the current fiscal policy situation. The first is a change in the treatment of the Bank of England’s balance sheet in the government’s fiscal targets which has had a big influence on why there has been such a swift move towards austerity. The second is the Bank’s policy on paying interest on reserves to commercial banks which provides an example of an alternative policy available to the tax increases and spending cuts being implemented.

What is the UK’s Fiscal Black Hole?

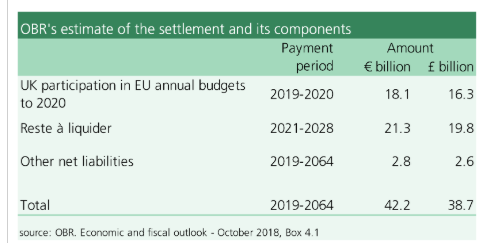

The so-called black hole stems from set of fiscal targets that the UK government has set itself and which are measured and monitored by the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR). As of now, the principal targets are that the current budget (excluding capital spending) be balanced by the third year of the OBR’s forecast and that a measure of net debt as a share of GDP be declining in the third year.

Of these two targets, the net debt target is likely to be the more binding now because it includes debt generated by capital spending and because the OBR’s forecast is going to include a decline in GDP due to the upcoming recession, thus raising the debt ratio. The Resolution Foundation have a detailed pre-budget presentation which points to the net debt rule as the key likely driver of the size of the consolidation.

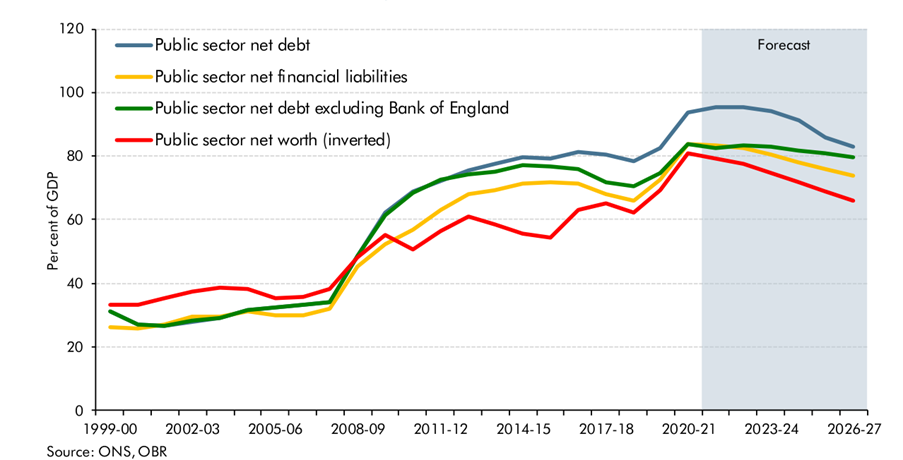

The most recent forecasts from the OBR for the net debt to GDP ratio are from March. Their March forecasts for various measures of the net debt to GDP ratios are shown below. Since late 2021, the measure chosen by the government for its target has been “public sector net debt excluding Bank of England”, the green line below. You can see that as of March, the projection for this series was that it would be flat to slightly declining in the coming years, just about in compliance with the rule.

Since March, several factors have worsened the fiscal outlook. The Bank of England has raised interest rates, increasing the cost of servicing public debt. The projected recession will reduce forecasted tax revenues and raise welfare spending and the government’s energy package will be expensive. Given all this, it is expected that without adjustments in the upcoming budget, the target measure of net debt to GDP will move upwards over the coming three years. This is the “black hole”: It is the amount of spending cuts or tax increases required to get this net debt to GDP measure falling in the third year of the forecast instead of increasing.

To many, the idea of having rules to ensure sound fiscal policy may seem sensible. However, there is little agreement among economists about the form such rules should take or indeed whether fiscal rules are a good idea at all. The UK has had various fiscal rules since 1997 and it is not clear they have been particularly helpful. A 2021 survey of macroeconomists by the LSE Centre for Macroeconomics showed about half believed fiscal rules had harmed the UK’s economic performance and nearly one-third favoured scrapping fiscal rules altogether.

One problem is that the specific rules being followed are essentially arbitrary, either relying on special “magic numbers” for debt or deficit levels (3% and 60% ring a bell for anyone?) or specific horizons over which certain objectives should be met. The UK’s current fiscal rules are new, having been announced in the 2021 budget. These new rules changed the debt target from total public sector net debt (the blue line above) to the measure excluding the Bank of England, which showed a lower net debt level. The rules were also changed from requiring a reduction in the net debt as a share of GDP over the next year to having it fall by the third year of the OBR’s forecasts. On their own, these were both sensible changes but (as I will discuss below) the change in net debt definition turned out to have unintended consequences.

So that’s the black hole. It is not in any way a pressing matter in which the UK is on the brink of “running out of money”. It is a consequence of an arbitrary rule the government has imposed upon itself with its specific form having been set just over a year ago. Had the UK government set a longer time horizon for the net debt ratio to be falling or used a different definition of the net debt ratio, the black hole would be smaller or perhaps non-existent.

Rather than sensible macroeconomics, deciding to impose a large fiscal contraction right as the economy is heading into recession runs counter to conventional macroeconomic wisdom. While the Truss-Kwarteng “let it rip now” approach to fiscal policy was clearly badly timed given current inflationary conditions, the alternative of swinging towards a big fiscal contraction to be implemented as the economy enters recession is also inappropriate. UK fiscal policy should be neutral for now but the normal approach of allowing “automatic stabilisers” to accommodate increases in welfare spending and reductions in tax revenues should operate once the economy goes into recession.

As a sign of how this austerity is badly timed, it is being widely reported that the OBR will calculate the contractionary effects on GDP of the upcoming fiscal austerity, which will worsen the projected recession and further increase the net debt to GDP ratio thus widening the so-called black hole. A chunk of this hole is being dug by the austerity itself.

But What About Markets?

What about the idea that austerity is needed to satisfy financial markets, the so-called bond market vigilantes? For many, the moral of the Truss-Kwarteng experiment was that markets require fiscal discipline and a failure to balance budgets raises the cost of borrowing and further worsens the public finances. I think this is a misinterpretation of what happened in September.

Without doubt, September’s financial market events in the UK were extraordinary but much of the turmoil related to forced selling of gilts by pension funds. While dramatic, these events were due to short-term “market plumbing” issues and were resolved fairly quickly. Beyond these short-term stresses, the key substantive macroeconomic problem was that Truss and Kwarteng introduced a set of fiscal policies that would have stimulated the economy right at the time when the Bank of England was acting to cool the economy to bring inflation down.

For some, there was also a concern that the Truss government would undermine the independence of the Bank of England and thus that higher inflation would be implicitly tolerated over the medium-term. These concerns will have required additional inflation-related compensation for investors in UK government bonds.

With Truss deposed and most (but not all) of Kwarteng’s tax cuts reversed, investors are no longer concerned that UK fiscal policy will exacerbate the current inflation problem or that the government will undermine the Bank of England’s independence. UK bond yields are up since the summer but not by much more than in other countries, all of which are also facing a persistent inflation problem and going through a monetary tightening.

Are the markets now baying for a return of austerity? I don’t think so. There was no sense prior to the Kwarteng fiscal measures that financial markets were requiring a large fiscal contraction to be willing to hold the UK’s debt and those measures have now been reversed. Also, there is nothing especially high or worrisome about current or projected levels of UK public debt. The UK gross government debt to GDP ratio for this year is about 100%, close to the average for the euro area and well below the 112% in countries like France, where nobody is claiming that financial markets are demanding austerity.

Of course, if Jeremy Hunt were to announce a much smaller austerity package than expected on Thursday, perhaps by adopting a new looser set of fiscal rules, it is possible that markets could react badly and raise long-term bond yields. However, I think a neutral budget that neither adds to the current inflation nor worsens the upcoming recession would be accepted by markets as a reasonable fiscal Ying to the Bank of England’s contractionary Yang.

The Strange Tale of the Bank of England’s Phantom Debt

One of the stranger aspects of the current turn towards austerity is the influence of a technical change in the chosen debt target. In the EU, debt targets are framed in terms of gross government debt and assets owned by governments are not considered. The EU rules also do not incorporate central banks, keeping their assets and liabilities “off balance sheet.” Until last year, the UK government’s chosen debt target differed from the EU’s approach both by subtracting off some assets and thus being a measure of “net debt” and also by incorporating the balance sheet of Bank of England.

This approach could have produced sensible net debt measures but the actual implementation did not. The Bank of England’s balance sheet shows its assets and liabilities. Its principal liabilities are the reserve accounts that commercial banks maintain with the Bank. The Bank acquired its QE portfolio and made loans to commercial banks via making credits to these accounts. These reserve accounts are liabilities for the Bank because it has a policy of paying interest on reserves. The Bank publishes its balance sheet weekly but a more accessible version is available in its 2022 annual report, which shows its February 2022 balance sheet.

The balance sheet shows that the Bank’s assets slightly exceed its liabilities. In fact, its true net position is better than this. Its balance sheet includes £86 billion in sterling bank notes in circulation that both the Bank and OBR count as liabilities. Since these are perpetual zero-interest notes, they have no cost to the Bank and so the Bank effectively has assets that well exceed its genuine liabilities. The key point here is The Bank of England has no net debt.

Despite this, the OBR made two decisions when constructing its net debt measure that meant incorporating the Bank of England’s balance sheet produced higher rather than lower net debt figures. First, the OBR decided to not include the assets the Bank acquired under its Term Funding Scheme (TFS), which loaned money to banks, while at the same time OBR decided to include the reserves that were created by the TFS loans as liabilities. OBR did this because they decided to only include liquid assets when “netting off” assets against liabilities and they decided the TFS loans were not liquid.

I don’t know why OBR considered the TFS loans to not be liquid. The Bank would never need to sell these assets so it’s an “angels on pins” discussion anyway but the loans are fully collateralised, so I’m sure the Bank could sell them fairly easily if it ever decided to do so. Anyway, in reality, the TFS scheme did not have any negative effect on the net debt of the Bank of England or the wider public sector but the OBR decided to measure it as though it did.

Second, the OBR measures the Bank’s gilt holdings acquired via QE at their face value while measuring the reserve liabilities created at the market value of the bonds purchased. Bond yields and prices move inversely, so the decline in yields during the Bank’s QE programme meant they bought bonds for market prices that were above the face value. For almost all of the post-QE purchases, the yields on the gilts purchased were higher than the interest on reserves, meaning it made profits on these investments but the OBR decided to make these transactions look like they made the Bank on net worse off.

In terms of the mechanics of how QE affected the public finances, the Bank passed most of the interest payments on its gilts back to the government, so effectively the QE programme refinanced UK government debt at the low interest rate paid on reserves and this saved the public sector money. Again, however, the OBR accounting made it look like a programme that increased UK net indebtedness.

Ultimately, central banks that print their own currency and can create money at the touch of a button are a source of revenue for governments. If your accounting says this part of the public sector has a negative net asset value, you’re doing something wrong.

Taken together, the OBR’s two dubious measurement decisions meant the incorporation of the Bank of England added a large amount of “phantom debt” to the OBR’s net debt measure. For 2021/22, the total net debt is estimated to be 95.5% of GDP while the net debt excluding the Bank of England is 82.5% of GDP. But (and this bit is important ….) the two key drivers of the phantom net debt—the TFS and the QE holdings—are projected to wind down in the coming years, so the phantom net debt declines from 13% of GDP in 2021/22 to only 3% in 2026/27.

Given how bad the OBR’s methods for incorporating the Bank of England are, the Treasury were clearly correct to switch from “net debt” to “net debt excluding the Bank of England”. The OBR itself has effectively admitted the new measure is better, saying in their March report that this change “removes the uneven effects across years caused in particular by the TFS”.

Now one might imagine that changing to this new measure would have caused there to be less pressure to introduce austerity. The new measure both makes more sense and shows lower net debt levels. However, as Rob Calvert Jump and Jo Michell have noted, this is not how things work in the world of UK fiscal rules. The new measures have increased the need for austerity.

Imagine the scenes at the Treasury after the new, better, net debt measure has been adopted.

Normal Person: “Hey look we’ve got a new measure of net debt that excludes all the phantom debt previously included by the OBR. Surely this means we don’t have to worry quite so much about debt now?”

Fiscal Rules Guy: “Well no, actually we need to worry more about debt than before. We need more spending cuts and tax increases”

Normal Person: “Why?”

Fiscal Rules Guy: “Well the new measure of net debt is lower but it doesn’t fall anymore over the next few years like the old measure did, so we need austerity.”

Normal Person: “But the old measure only fell because the non-existent phantom debt declined. Are we really introducing austerity because we stopped counting the non-existent debt?”

Fiscal Rules Guy: “Rules are rules dear fellow.”

Suffice to say 10% of GDP is a lot of spending to cut or taxes to raise over the next few years and this measurement change as a rationale for a bunch of extra austerity doesn’t fit well with common sense.

Interest on Reserves

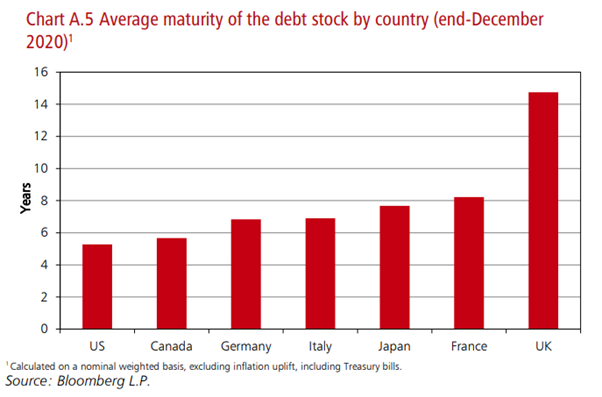

The other way the Bank of England impacts the budget is that the Bank pays interest on reserves at its “Bank rate.” With the Bank raising interest rates, these additional payments to commercial banks will reduce the profits of the Bank of England. As a result, the Bank will go from passing profits on to the Exchequer to not doing so and, if the Bank makes losses, it may be years before it returns to passing on a dividend to the Treasury. Effectively, the Bank’s payments of interest on reserves represent a one-for-one fiscal cost for the public sector.

The payment of interest on reserves is a modern phenomenon. The Bank of England started paying interest on reserves in 2006, so there is no long tradition of banks receiving compensation on their reserves. This changed with the introduction of QE by the world’s central banks.

Prior to QE, central banks had raised interest rates by engineering a shortage of reserves, so that banks were willing to pay high interest rates to borrow funds from each other. After QE, there was no shortage of reserves, so central banks had to find another way to raise interest rates, if this was what monetary policy called for. They did this by paying interest on reserves. A bank that received a 4% interest rate just for keeping money with the central bank would not be willing to make loans at lower rates than this, so the interest rate paid on reserves became the floor for market interest rates.

When interest on reserves was first introduced, there weren’t many discussions of its fiscal impact these are now significant. For example, as of November 2nd, UK banks had £950 billion in reserve balances. If the Bank of England were to compensate those reserves at a 4% interest rate, this would imply interest payments of £38 billion per year.

Are these payments required to implement the higher interest rates the Bank wants for its monetary policy? No. It is widely understood in central banking that what is required is only that the marginal reserves in the system are paid the interest on reserves. The government doesn’t need to compensate all the reserves a bank holds. It just requires that the marginal pound of reserves that a bank holds would receive this compensation. This “tiering” approach has been used by both the Bank of Japan and the ECB, albeit in the context of negative interest rates, so that only some of the reserves that banks held with them were subject to the negative rates. But the logic that it was the marginal reserves that mattered for market rates worked perfectly.

The idea that central banks do not need to compensate all reserves may not have been discussed much in the context of the “black hole” but it is hardly a radical and dangerous idea. Former Bank of England Deputy Governor, Sir Paul Tucker, a pillar of the international central banking establishment, has proposed tiering in a recent paper, arguing the fiscal savings could be £30 billion and £45 billion over the next two budgetary years. These are large figures and would account for a big fraction of the tax increases and spending cuts being considered.

Some argue that failing to pay interest on reserves amounts to a tax on the banking sector. I don’t think this is correct. Taxes are deducted from income earned or wealth held and this policy does neither of these things. Banks holding an asset that doesn’t receive any compensation may reduce their profits but central banks have long adopted policies that either boost or reduce bank profits and these have never been labelled fiscal policies. At the end of the day, however, if the failure to compensate all reserves means bank shareholders lose money or depositors earn a lower interest rate on deposits, then there are strong arguments that these outcomes would represent a fairer way to stabilise public finances than the other options being considered.

Rather than argue that introducing tiering would be the Bank of England stepping into fiscal policy, I would describe this issue in a different way. Interest on reserves is a monetary policy. It was introduced to allow central banks to set specific levels of market interest rates and thus meet their inflation target goals. However, central banks are public bodies and there is no public policy case for central banks to spend public money if it does not actually help the central bank meet its specified objectives. Because compensating only reserves above a specific level works to allow central banks to meet their monetary policy objectives, there is no monetary policy rationale for compensating all reserves. In other words, deciding to pay interest on all reserves is the Bank of England stepping into fiscal policy, rather than sticking to its monetary policy mandate.

There Are Alternatives

It has been a whirlwind few weeks and there are several compelling moral narratives that have convinced many that the UK needs to implement an extremely harsh budget. Covid and energy packages surely must be paid for. The sins of Truss and Kwarteng’s profligacy surely must be atoned for. Sensible fiscal rules surely must be obeyed. The costs of Brexit must surely be finally faced up to. And the Bank of England’s independence surely rules out any discussion of its policies being altered because of their fiscal implications.

The reality, however, is that the UK’s public debt position is in the middle of the international pack and there are almost no discussions in other countries with similar debt levels of the need for a new round of austerity. And if the UK government wants to reduce its fiscal deficit, it is reasonable to ask whether payments that benefit bank shareholders and depositors should be protected while cuts are made to public services that are already threadbare.

Coda: Since I wrote this yesterday, I have read these (much shorter) pieces by Giles Wilkes and Duncan Weldon that cover some similar ground. (Hat tip to Stephen Bush’s excellent Inside Politics newsletter.) I think I agree more with Duncan than Giles but both are worth a read if you’ve made it this far.