A few points on the £39 billion payment which the UK government has agreed to pay the EU as part of the withdrawal agreement.

This payment is regularly raised by Brexiters as a key negotiating issue. It is often claimed the £39 billion saved by refusing to make this payment will allow the UK to spent lots of money on important priorities e.g. Priti Patel says “we would also not need to hand £39 billion over to the EU, giving the Government resources to support economic growth, job creation and new trade opportunities.” It is also claimed the EU are very scared the payment won’t be made and will thus make last concessions to secure the money e.g. Daniel Moylan at BrexitCentral reckons “It is possible that the EU could give in, agreeing the wholesale removal of the Irish backstop from the text in exchange for the money on which they have so desperately counted.”

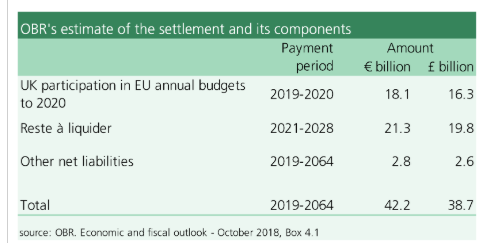

The reality, however, is that both sides of this argument – the benefit to the UK and the costs to the EU – tend to be wildly over-stated by Brexiteers. Here is a useful table from a House of Commons Library explainer on the topic, breaking down the different elements of the £39 billion.

The table shows that the £38.7 billion bill includes £16.3 billion in contributions to the EU’s multi-annual budget during the transition period. During this period, the UK will continue to receive funding from EU programmes.The House of Commons Library report estimates the UK will receive about £8 billion of this funding back during 2019-20 in the form of payments to farmers, structural funds and funding for research (see page 8). These payments would not occur if there is no deal. This means the financial “benefit” to walking away from the withdrawal agreement would really be £31 billion, albeit at a cost of the UK being seen to have reneged on financial commitments it made to its EU partners.

Second, this net payment of £31 billion would be spread over time. Scrapping the additional net contributions to the EU budget would amount to saving of £4 billion per year this year and next. The rest of the payment is spread over time, with the bulk of it, £19.8 billion, being paid over 2021-28 and a smaller amount of £2.6 billion being paid over 2021-64. That works out to be a benefit of £2.5 billion per year over 2021-28 and £56 million per year thereafter until 2064.

How much will the UK government be able to do with this money? UK GDP was £2 trillion pounds in 2017. A trillion is one thousand billion, meaning the £4 billion savings this year and next would be one fifth of one percent of UK GDP and the £2.5 billion per year savings over 2021-28 would be about one eighth of one percent of UK GDP.

So while £39 billion may seem like a huge figure when quoted without context, the reality is that this will do very little to boost the spending power of the UK government. In fact, these numbers are well below the kinds of figure by which UK budgets often overshoot or undershoot doing to various random events without anyone paying much attention e.g. the OBR’s March 2017 forecast of the budget deficit over 2017/18 was £17 billion too high (see page 35). The dividend from not paying the Brexit bill will effectively be rounding error in the public finances.

And what about the EU27? The £2.5 billion net payment per year the EU would be losing over 2021-28 equates to €2.8 billion euro per year. EU27 GDP is estimated to be €14.538 trillion last year. That’s €14,538 billion. So this loss would equate to 0.02 percent of EU27 GDP per year for eight years. That’s one fiftieth of one percent of GDP. The idea that this tiny amount is being “desperately counted on” by the EU is laughable and anyone relying on the EU to fold because the UK won’t pay its “Brexit bill” will be sorely disappointed.

The bottom line on this issue is that, viewed from a macroeconomic perspective, the Brexit bill figures are tiny and people really should not believe that this bill represents an important part of the costs or benefits of Brexit for either the UK or the EU.

There is a wider issue here in relation to explaining macroeconomic issues to the public. Any figure larger than a few million seems to ordinary people to be “a lot of money”. So “£350 million pounds per week for the NHS” or “£39 billion to spend on whatever we want” seem like huge windfalls to a large fraction of the public who, let’s be fair, can’t be expected to know the actual totals for GDP or public expenditure. It’s thus important for those contributing to public debate to put raw macroeconomic numbers in an appropriate context.