After a chaotic two months in British politics and with little time remaining before the UK is set to leave the EU, its parliament has now requested the EU replace the crucial backstop protocol in the Brexit withdrawal agreement with some other set of unspecified “alternative arrangements.” The Prime Minister reversing course on the deal she agreed after two years of intensive negotiations was never likely to go down well with the EU27 and the immediate negative response from Donald Tusk suggests there will be no re-opening of negotiations.

Simply ignoring this latest request may work out for the EU. After a few more weeks without progress, enough MPs may finally decide that the impending chaos of no deal is worse than the deal Theresa May agreed to in November and which is still on the table. The UK could end up signing up to the November agreement, though this would be seen as a humiliating outcome for many of the politicians who enthusiastically voted for last night’s “Brady amendment”.

There are a number of reasons, however, why the EU, and particularly Ireland, should be wary of pursuing this strategy and I suggest they should consider an alternative route involving a clarification and a concession on the backstop.

The reasons to be wary?

First, without further negotiations or concessions, it is possible that the UK parliament may end up delivering a no-deal outcome that very few profess to want. In the absence of a deal that can pass the House of Commons, even after a potential delay of the Article 50 process, the no-deal crash out becomes the default option and odds on it continue to rise. The Brady vote has probably entrenched some Conservative MPs into a position they will find difficult to give up without some movement from the EU. It may make no economic sense whatsoever for the UK to exit without a deal but Brexit has never made economic sense and its most intense advocates are growing ever more determined to leave at almost any cost. The EU member state that would be most damaged by this outcome would be Ireland.

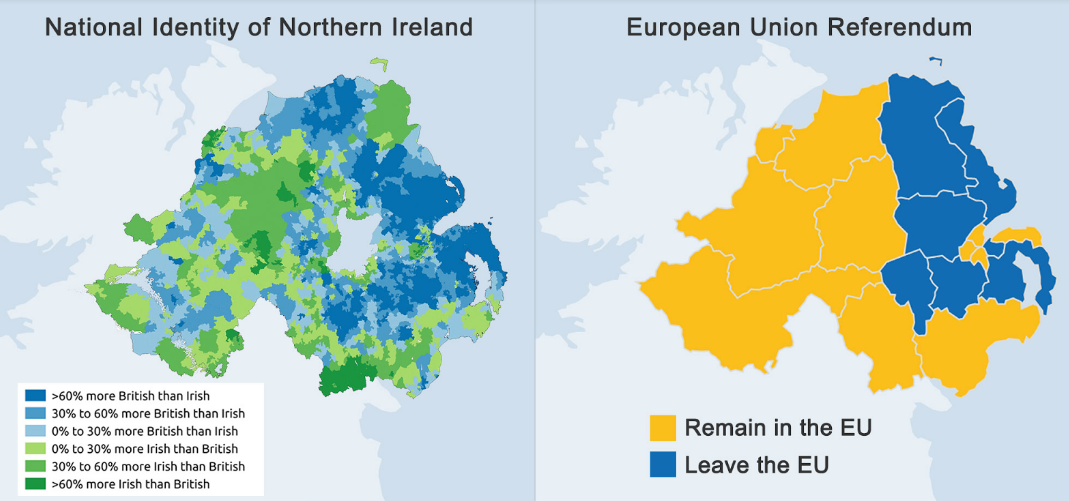

Second, the strategy of providing no response at all to the Brady vote could poison EU\UK relations and their North\South equivalent in Ireland for many years even if the November agreement is eventually passed. Many in the UK will feel, rightly or wrongly, that they were bullied into the agreement by the EU without appropriate considerations for the perceived problems associated with the backstop. In Northern Ireland, the DUP will claim the backstop was imposed by the EU against the preferences of a majority of the House of Commons. Unionist objections about a lack of democratic legitimacy of the backstop, in which Northern Ireland remains subject to EU regulations and customs rules but has no say in deciding those rules, will continue to be a cause of discontent for many years.

So what could the EU do to respond to last night’s vote?

A Clarification

Firstly, the EU could clarify that it has no objections to the UK leaving the joint customs union with the EU after the transition period, provided Northern Ireland remains within the EU’s customs union and aligned on goods regulations.

Brexit wonks could argue that this clarification shouldn’t really be necessary since this is the original version of the backstop that the EU offered, so it should be clear they are willing to still offer this. The all-UK backstop was a hard-won concession to the UK. It reduced the amount of trade disruption to be experienced over the medium-term by the UK while it was still negotiating trade deals with the EU and the rest of the world, and it prevented the need for customs checks on goods going from Great Britain to Northern Ireland.

Still, the nature of the all-UK version of the backstop does not seem to have been well understood in Westminster, partly because Theresa May never spent any time explaining its benefits. Instead, among Brexiters, it has become widely held that this all-UK backstop is an attempt to “trap” the UK permanently within EU structures and hamper it from successfully negotiating its own trade deals.

A simple clarification from the EU on this issue, to be added to the political declaration, could help to resolve this unnecessary confusion about the all-UK backstop.

A Concession

That still leaves the question of the Northern Ireland element of the backstop. Theresa May probably did not devote much political capital to selling the fact that Great Britain could move out of the backstop without difficulty provided Northern Ireland remained in it because she was determined to keep the DUP on board and they would not have been pleased with this being sold as a positive feature. As it is, in addition to losing many Tory colleagues who disliked the all-UK backstop, May also failed to get the DUP to support her November agreement and has now acceded to their request that she ask the EU to modify the backstop.

So what can be done? The motivations of the EU and Irish government for the backstop proposal are well known and there are severe limits on how much they can move. Moreover, the nebulous mooted “alternative arrangements” to the backstop mentioned in the Brady amendment don’t present a useful basis for current discussions.

However, the EU could do the following: Use the political declaration to offer the citizens of Northern Ireland a referendum on whether to remain within the EU’s customs union and single market five years after the beginning of the operation of a Northern-Ireland-only backstop. This referendum could be repeated at perhaps ten-year intervals thereafter. Should a referendum show the people of Northern Ireland wanted to exit the backstop, the EU would agree jointly with the UK to end this arrangement.

I have proposed the idea of a referendum within Northern Ireland before, back in November 2017. I still think an approach of that sort should have been considered and polling suggests the backstop would have received majority support. It is too late now to consider a referendum of this sort prior to the UK exiting the EU. However, a promise to hold a referendum five years after the end of the transition period would provide a clear concession to those who believe the backstop arrangements would be harmful to Northern Ireland by offering them a chance to convince their fellow citizens to end the arrangements after a period.

This proposal would also give the citizens of Northern Ireland a number of years to experience “life in the backstop” and to consider the benefits and costs associated with it before making their own decision about whether to continue with this arrangement. I have detailed previously how the backstop would probably provide some important benefits for the Northern Ireland economy and that the perceived intra-UK frictions associated with it are likely to cause only minor difficulties compared with the far larger problems associated with a hard intra-Irish border. The costs and benefits of being excluded from future UK trade deals may also become more apparent. I suspect it may turn out that Northern Ireland consumers and farmers won’t actually be too concerned about missing out on the chlorinated chicken and hormone-injected beef brought about by trade deals with the United States or South American countries.

The Irish government and EU could also offer to work to address concerns about the “democratic deficit” associated with the backstop. It may be possible for Northern Ireland to have non-voting members of the European Parliament or for the Irish delegation of MEPs to include a couple of delegates elected via votes from those in Northern Ireland. The EU could regularly hold workshops and listening tours in relation to upcoming regulatory changes that could affect Northern Ireland as long as it remains in the backstop.

Another benefit of this proposal is that it would allow at least seven years for the UK and Irish governments to explore more fully the options for “smart border” technologies which have been widely promoted by some and heavily doubted by others. A well-funded joint project by the EU and UK on the possibilities available could be prepared to provide concrete information to Northern Ireland’s voters on the way the border would operate should they ever choose to leave the backstop. My guess is that no matter how smart the technologies, a hard border of some sort would be required if the backstop is removed but this proposal would give Ireland and the EU at least seven years to prepare for this potential outcome.

The danger of this approach from the perspective of the Irish government is that it may only kick the can of a hard border down the road by seven years or more. But it may also help to avert a no-deal Brexit and provide invaluable time to prepare Irish firms for potential future arrangements. One could also argue that if the backstop arrangements cannot receive majority support in Northern Ireland over time, then they are probably not politically sustainable anyway.

Would This Be Enough to Get the Deal Through the UK Parliament?

Would these clarifications and concessions be enough to avert a hard Brexit? It’s hard to know but a final attempt at outreach could at least convince some MPs that the EU and Ireland have listened and addressed their concerns about the UK’s ability to conduct future trade deals and the democratic legitimacy of the backstop for Northern Ireland.

I suspect the DUP will not accept a proposal of the sort outlined here but these ideas may be enough to convince sufficient numbers of Tory waverers and Labour leavers that the deal on the table represents a better outcome than no deal. In addition to helping pass the withdrawal agreement, a final effort of this sort from Ireland and the EU could hopefully also set a tone for a more co-operative future relationship with the UK.