Seventeen months on from the Brexit vote, the UK government has largely avoided setting out clear and realistic positions on key issues. Their stance on almost everything continues be a form of cake-and-eat-it.

Nowhere is this more clear than on the question of the Irish border. The UK’s position is that there will be no hard Irish border even though they plan to take the UK out of the EU’s single market and customs union. When pressed on this, they use the phrases “flexible and imaginative” and “technologies” but don’t put forward much by way of specifics. (If you think I’m exaggerating, read this).

In the absence of anything concrete from the UK government, the EU has put forward its own flexible and imaginative suggestion that Northern Ireland could remain part of the EU’s single market and customs union. This proposal has been received negatively by the Conservative Party and the DUP. As best I can tell, there has been little public discussion of the objections that have been put forward, so here I want to discuss the economic arguments for and against the EU’s proposal and to propose that Northern Ireland be allowed vote on it.

The Economic Arguments

If Northern Ireland were to remain part of the EU’s single market and customs union, then this would allow free movement of goods between the North and South of Ireland. However, once the UK leaves the EU’s single market and customs union, then there would need to be some form of checks on goods leaving Northern Ireland for Great Britain as well as those goods coming in the other direction. The extent of these checks would depend, over time, on the extent to which the UK departs from its current EU-consistent policies on tariffs and regulations.

One economic argument against this proposal is that Great Britain is a more important market for Northern Irish firms than the Republic of Ireland and the rest of the EU. Figures show that in 2015, Northern Ireland had €14.4 billion in final sales to Great Britain while final sales to Ireland were €2.9 billion and sales to the rest of Europe were €2.1 billion. In this sense, surely it makes sense from an economic perspective for Northern Ireland to rule out any trade barriers with Great Britain?

There are two counter-arguments to this position. The first is that the final sales figures under-state the significance of cross-border economic linkages to Northern Ireland. The second is that the inconvenience to firms of NI\GB trade costs will likely be much smaller than the costs associated with an Irish border for goods.

Importance of the All-Ireland Economy

The trade figures just described come from an appendix to the UK government’s position paper on Northern Ireland and Brexit. However, the paper also acknowledges that

the sale of finished products to Great Britain relies upon cross-border trade in raw materials and components within integrated supply chains meaning trade with both Great Britain and Ireland are vital to Northern Ireland’s economy.

And that cross-border trade is a crucial part of the Northern Irish economy:

Over 5,000 businesses in Northern Ireland exported goods to Ireland in 2015, one and a half times as many as sold goods to Great Britain.

So cross-border trade clearly plays a very significant role in Northern Ireland’s economy. In addition to these substantial linkages, there are also a wide range of all-Ireland bodies devoted to supporting all-Ireland economic linkages in areas such as agriculture, the environment, energy and so on. Northern Ireland leaving the EU’s single market would likely undermine the economic benefits that have been achieved in these areas.

A Seamless Irish Border?

Once the UK leaves the EU’s customs area and agrees new trade deals with third-party countries, then the EU will require an Irish customs border to protect the integrity of its customs union. There is no point, by the way, in presenting this as a “big undemocratic EU bullies little Ireland” story: There is no way Irish farmers will allow the UK to pursue cheap food deals with the US or Brazil and then have these products imported to the Republic without customs checks.

Brexiteers are currently saying the EU will be “to blame” for the subsequent border checks but the border will only be there because of the UK’s decision to leave the EU. Moreover, despite silly talk from various British politicians about the UK “not being bothered” to enforce a customs border in Ireland, the UK will be under legal obligations to do so via its WTO commitments.

So if Northern Ireland leaves the single market, the customs union and European Economic Association (EEA), there will be border-related checks on goods: Customs checks, rules-of-origin checks, regulatory compliance checks. Will the much-discussed technological solutions make all of this seamless? No

Some in the British press have pointed to the Sweden-Norway border as an example of how well an Irish border could work. For example, this BBC report starts with stories about average wait times of eight minutes and plans for a future frictionless border. Only later in the story do we find “there is still plenty of paper to be processed, first with the customs agents, then at the customs office” and that the eight-minute figure might have been over-hyped. “A Swedish trucker grumbles to me that it can take an hour and a half, and he is unimpressed with the level of customer service.”

For lots of reasons, an Irish customs border will be more complicated. For starters, unlike Norway, the UK will be leaving the EEA, meaning extra layers of trade and regulatory checks will be required that do not exist on the Norway-Sweden border. Another important difference is the political sensitivities of border checks in Northern Ireland and the possibility that formal checkpoints could be a target for terrorist organisations.

The complexities of the physical Irish border are also daunting. Currently, there are an estimated 1.85 million cars crossing the border each month through about 200 crossing points as well as 208,000 light vans and 177,000 lorries. And the nature of the border they are crossing? Here’s Fintan O’Toole

It meanders for 310 miles, and it is not a natural boundary. It was never planned as a logical dividing line, still less as the outer edge of a vast twenty-seven-state union. It is simply composed of the squiggly boundaries of the six Irish counties that had, or could be adjusted to contain, Protestant majorities in 1921. And it cannot be securely policed. We know this because during the Troubles it was heavily militarized, studded with giant army watchtowers, overseen by helicopters, and saturated with troops—and it still proved to be highly porous. It is an impossible frontier.

Trade Costs Associated with an Irish Border

Even if physical customs borders managed to be relatively seamless, Northern Ireland leaving the customs union would still damage many of the businesses that rely on integrated cross-border supply systems. To give one example, consider the example of dairy businesses in which milk from Northern Ireland is moved over the border for processing, then perhaps moved back to the North for further processing and then perhaps sold in the Republic. When Michael Lux, a German customs expert and former European Commission employee was asked about these kinds of businesses by a House of Commons committee, he responded

“I am always saying to companies, “You need at least two people doing the customs business, if you do it yourself, because one of them may be ill or on holiday and then you will have nobody to do it.” Alternatively, you can use a service provider that is a logistics company. Depending on the complexity, they will charge you between €20 and €80 per declaration; so the cost will increase enormously just due to the fact that, each time you are doing something that involves a crossing of the border, it creates a cost. That will be part of the cost of the milk and, later, of the cheese, and I cannot imagine that anybody will continue these practices. It would just be too costly.”

Manufacturers in Northern Ireland are gradually learning how costly it would be for them to leave the customs union. Stephen Kelly, Chief Executive of Manufacturing Northern Ireland, told a Commons committee:

I have some evidence here for the Committee today, on just what that country-of-origin certification and the paperwork around that would actually mean in terms of cost to an individual business. Between the development and the time required to produce those certificates, plus the letters of credit from banks that are required to export alongside, the total is £478 per shipment. That is roughly the same price as shipping a container from Northern Ireland to GB or two-thirds of the price of shipping a full container from south-east Asia to Northern Ireland ….

the dangers that are staring our members directly in the face right now is a £478 charge every time they transfer anything across a border, and that is just the paperwork element of it, never mind any tariff elements

To summarise, even a sophisticated “light touch” implementation of an Irish customs border would involve delays and costs that would have a highly negative effect on businesses that have relied on integrated North-South supply chains.

Trade Costs Associated with Northern Ireland Remaining in the Customs Union

What about the alternative? Wouldn’t trade costs associated with Northern Irish firms moving goods to Great Britain also be a big problem? This is clearly not an ideal scenario but there are a number of mitigating points.

The first is that this is a much simpler “border” to monitor. Almost all of Northern Ireland’s trade with Great Britain is shipped via freight and two-thirds of this is shipped via Belfast port (see page 10 here). Goods are shipped already require various pieces of paperwork to be filled out, so it may be possible to add customs and regulatory forms to these and, yes, to use technology to ensure that all of the trucks arriving at Belfast port are ready to board with minimal delays. It would certainly be a lot easier than monitoring the famously-complicated Irish border.

A second is that it may be possible for the EU and UK to agree to designate Northern Ireland as a special economic zone that would allow streamlined procedures to make moving goods to Great Britain as cheap as possible. This could include exemptions from various regulatory or rule-of-origin checks for the vast majority of Northern Irish firms and a guarantee from the UK government that there would be no fees charged for any documentation required. I would guess the Irish government would be willing to share in the costs of administering the checks required in moving goods from Northern Ireland to Great Britain.

This outcome—remaining in the customs union and single market but with simple low-cost procedures for moving goods into the UK—could make Northern Ireland a highly attractive option for international firms. It would allow them to get direct access to EU markets while also getting lower-cost access to the British market. Designed in a flexible and imaginative way, Northern Ireland could potentially prosper as a result of its special status.

Movement of People

One complication when discussing Brexit is that when borders get discussed, most people immediately think about passport control and delays in travel for people moving through airports. Thus, the idea of Northern Ireland remaining in the EU customs union gets represented as a “border in the Irish sea” and people imagine that Northern Irish residents will have to go through passport control to get into Great Britain. In fact, Northern Ireland remaining part of the customs union and single market would likely have no implications for border controls for people. It would simply affect the movement of goods.

Both the Irish and British government seem committed to maintaining the “common travel area” which would allow Irish and British people to move freely between the two countries as well as maintaining other rights such as the right to work. I don’t believe anyone is suggesting Irish border controls to monitor people coming from the EU going to Belfast to then enter the UK.

Indeed, the whole focus on border controls as a way of keeping EU citizens out of the UK is misplaced. Unless the UK is planning to eliminate tourism from the EU, there will presumably be a bilateral agreement between the UK and EU on a light-touch visa-free system allowing tourist visits of sixty to ninety days. The UK will have to decide how to deal with those who overstay these visas but absent the right to work legally in the UK, I doubt if this is going to be a major problem. And there would really be little point in coming to Ireland to travel to Belfast to enter the UK with plans of working illegally since you could just go directly.

So let’s leave aside issues relating to passport controls: If Northern Ireland remains in the EU customs union and single market, its people will be able to move freely back and forth to “the mainland”.

The Politics

So that’s the economics of it. Neither of the options on the table are ideal and none will match the current level of market access enjoyed by firms in either the North or South of Ireland. But, on balance, a plan to keep Northern Ireland as part of the EU’s single market and customs union probably has more economic benefits for Northern Ireland than costs.

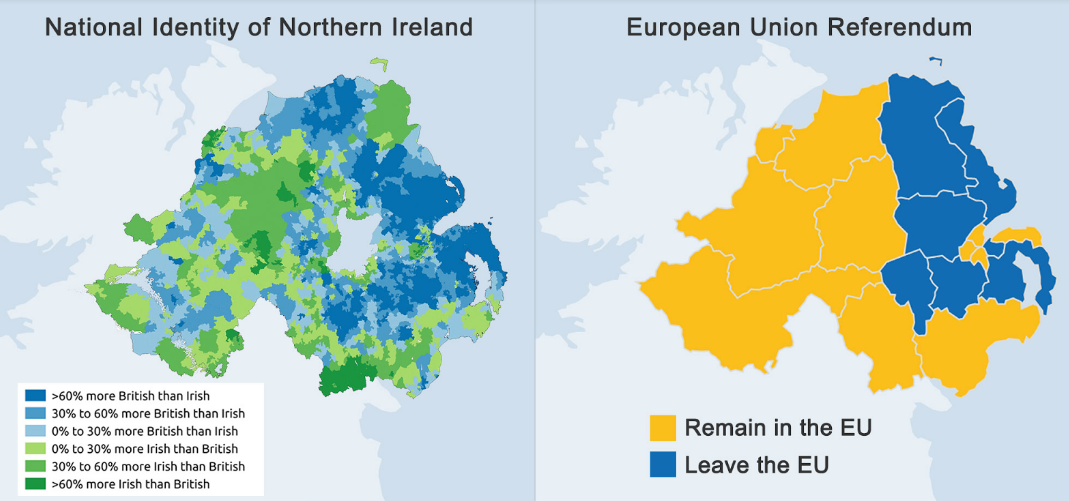

The politics are infinitely more complicated. The largest party in Northern Ireland, the Democratic Unionist Party (DUP) define themselves by their commitment to maintaining Northern Ireland as part of the UK and they resist anything that looks like it is loosening these links. Hence, the reaction of DUP’s leader to the EU’s proposal as “reckless” and all about the Irish government “getting the best deal for themselves”. Similarly, the Conservative Party seem dumbfounded at this idea, with the Secretary of State for Northern Ireland, James Brokenshire commenting “I find it difficult to imagine how Northern Ireland could somehow remain in while the rest of the country leaves. I find it impossible.”

DUP opposition to the EU proposal has also not been helped by implications that the proposal is part of an Irish plan to somehow fast-track reunification. I think this is misplaced. The current Varadkar\Coveney Irish leadership team strikes me as perhaps the least republican in Irish history. And one can believe this is the best proposal available without being in any way focused on a united Ireland. Personally, I would vote against a united Ireland if it was put to a referendum in the Republic and would worry greatly about the economic, political and security capacity of the Republic to successfully absorb Northern Ireland.

So even if worries about “a border in the Irish sea” (which sounds like every unionist’s nightmare) could be clarified and the economic costs of a hard Irish border explained, it is likely that most DUP supporters will accept the economic costs of the new Irish border rather than accept anything that looks like a step towards integration with the Republic. And to be fair, unionists may wonder what their status as UK residents actually means if they started to depart from the regulatory framework of a post-Brexit UK (e.g. if Northern Ireland didn’t get to be part of the Brexiteer vision of the UK as the Singapore of Europe).

The reality, however, is that Northern Ireland already differs sharply from the UK in lots of ways, including its form of government, rules on gay marriage and abortion and the plethora of ways in which the Good Friday agreement has introduced North-South co-operation. The proposal to stay in the customs union could be considered just an additional recognition that Northern Ireland is a very specific place with a special status and its impact may likely be far less obvious than the re-introduction of border controls on the island.

Also, DUP opposition to the EU proposal is not, on its own, reason to assume it should not be considered. The DUP only received 28 percent of the vote in the recent Assembly elections, with the anti-Brexit Ulster Unionist Party receiving 12 percent and the anti-Brexit anti-hard-border Nationalist parties receiving 40 percent. Indeed, many young people in Northern Ireland are moving past the simplistic Nationalist\Unionist identities and may consider voting for whichever option they believe will be good for their economic security.

A Proposal: Let Northern Ireland Decide

Northern Ireland voted against Brexit by a fairly comfortable 56 to 44 margin but that was a vote for all of the UK to remain in the EU. We don’t know how Northern Ireland would vote on a proposal to remain in the EU’s customs union and single market while the rest of the UK does not. But I believe the people of the North deserve the opportunity to make this decision.

A future Northern Ireland economic model dictated by either London or Brussels could prove to be a long-standing source of resentment to large numbers of people in the North. In contrast, a future economic model decided by a referendum would continue the approach of requiring democratic consent for major decisions that was established with the Good Friday agreement.

So my recommendation to the Irish government is as follows: Agree to allow the Brexit talks to move to Phase 2 in return for a commitment from the UK to hold referendum in Northern Ireland by May 2018 on the EU’s proposal for it to remain part of the single market and customs union.

This proposal gives both the UK and Irish government a way out of what currently seems to be an impasse: Ireland can claim to have found a route to maintain the all-Ireland economy, while the UK government can get on with what it really cares about (trade talks) without actually taking the decision to keep Northern Ireland in the single market and customs union.

Is it feasible for the UK government to implement this proposal given its parliamentary reliance on the DUP? I think so. The DUP will doubtless object to a referendum but a British parliamentary majority for the proposal should be easy to obtain with the support of the Labour Party. After they’ve decided whether to bring the UK government down (thereby losing all the money Theresa May promised them and potentially letting Jeremy Corbyn take over) the DUP can then campaign again to get Northern Ireland out of the single market and customs union. If people of Northern Ireland decided to agree with them, then everyone in Ireland would need to prepare for the border that would be the consequence.