Jean-Claude Juncker, Luxembourg prime minster and head of the Eurogroup of finance ministers has said that he believes that a Greek exit from the euro would be “manageable” Partially based on my recent experience of Ireland’s banking crisis, which was “manageable” until suddenly it wasn’t, I don’t take much reassurance from politicians using this phrase.

In many ways, this was a fairly typical intervention from Juncker, who has a touch of foot-in-mouth disease. His comments appear to have begun as a dismissal of German politicians saying they are not worried about Greek exit with Juncker pointing out “it would be better if more people in Europe kept their mouth closed more often”. Indeed. But then this particular piece of reassurance comes from the man who, when caught lying last year about an emergency finance ministers meeting on Greece, responded “When it becomes serious, you have to lie.”

So what’s the case for a Greek exit being manageable? One could argue that the euro existed for a time without Greece and functioned fine, that allowing Greece to join was a mistake, and thus that a euro without Greece would be more stable. While some of the countries that would remain in the euro also have severe debt problems, you could argue that they were not as intractable as Greece’s.

Finally, you could argue that the Eurosystem would provide full support to the governments and banks in the remaining countries provided, of course, that they don’t go the Greek route and fail to control their debt problems. In other words, some believe a Greek exit could reinforce the rules required to maintain the stability of the euro by showing that the core countries are serious about their enforcement.

I think these arguments under-estimate the seismic impact a Greek exit would have and I have severe doubts as to whether these impacts could be managed in a way that saves the euro.

A Greek exit would forever shatter the illusion that the euro is a fixed and irrevocable union. European politicians will claim that Greece is a unique case but they have made far too many false claims in the past to be considered credible.

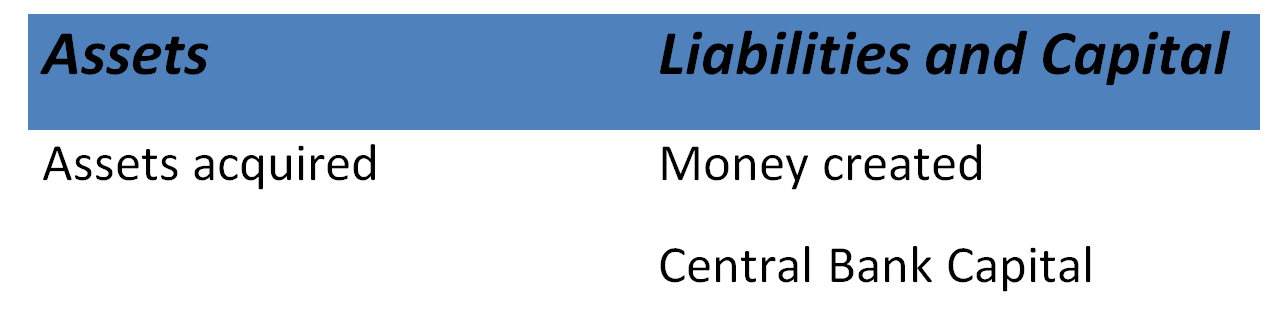

A Greek exit would likely trigger a massive flight of bank deposits from the periphery as the current “bank jog”—largely driven by large corporate accounts and non-residents—turns into a full retail bank run. If default on deposits is to be avoided, this would require a massive injection of central bank funding by the Eurosystem into these countries. This would raise severe tensions: Will Germans be willing to allow the Banca d’Italia to print enormous amounts of euros to facilitate Italians to move their money to Germany and have their deposits stand on an equal footing with German resident deposits after a euro break-up?

Another possible response to a bank run would be the introduction of euro-wide deposit insurance. However, this plan would only work provided it guaranteed that people retained the original value of their euro deposits even after they had been re-donominated into pesetas or lira. Otherwise, people will still have an incentive to move their money. But re-denomination insurance provides a huge incentive for countries to leave. People can have their debts re-denominated into a weaker currency and the EU will kindly pick up the tab in relation to the money people lose on their deposits. This proposal would not be acceptable to the core Eurozone countries.

A Greek exit would trigger a broad range of different legal problems as various parties sue each other to claim they are owed euros, not drachmas. The resolution of these problems would illustrate which kinds of parties are at risk when a country exits the euro and their Spanish and Italian counterparts would come under severe pressure.

A Greek exit would place pressure under peripheral Eurozone economies no matter what the outcome is. A disastrous post-euro outcome in Greece will convince many investors that any economy in the euro area at risk of leaving should be avoided. Alternatively, a healthy Greek rebound after the initial chaos would place pressure on governments in countries suffering inside the Eurozone that Greece is an example to be followed.

The European authorities may have some secret plan for holding the euro together after a Greek exit but, frankly, I have my doubts.